Short video feature on the Downtown Music Gallery. All videos: Hari Adivarekar

Don't feel like reading? Listen to an audio feature on the Downtown Music Gallery

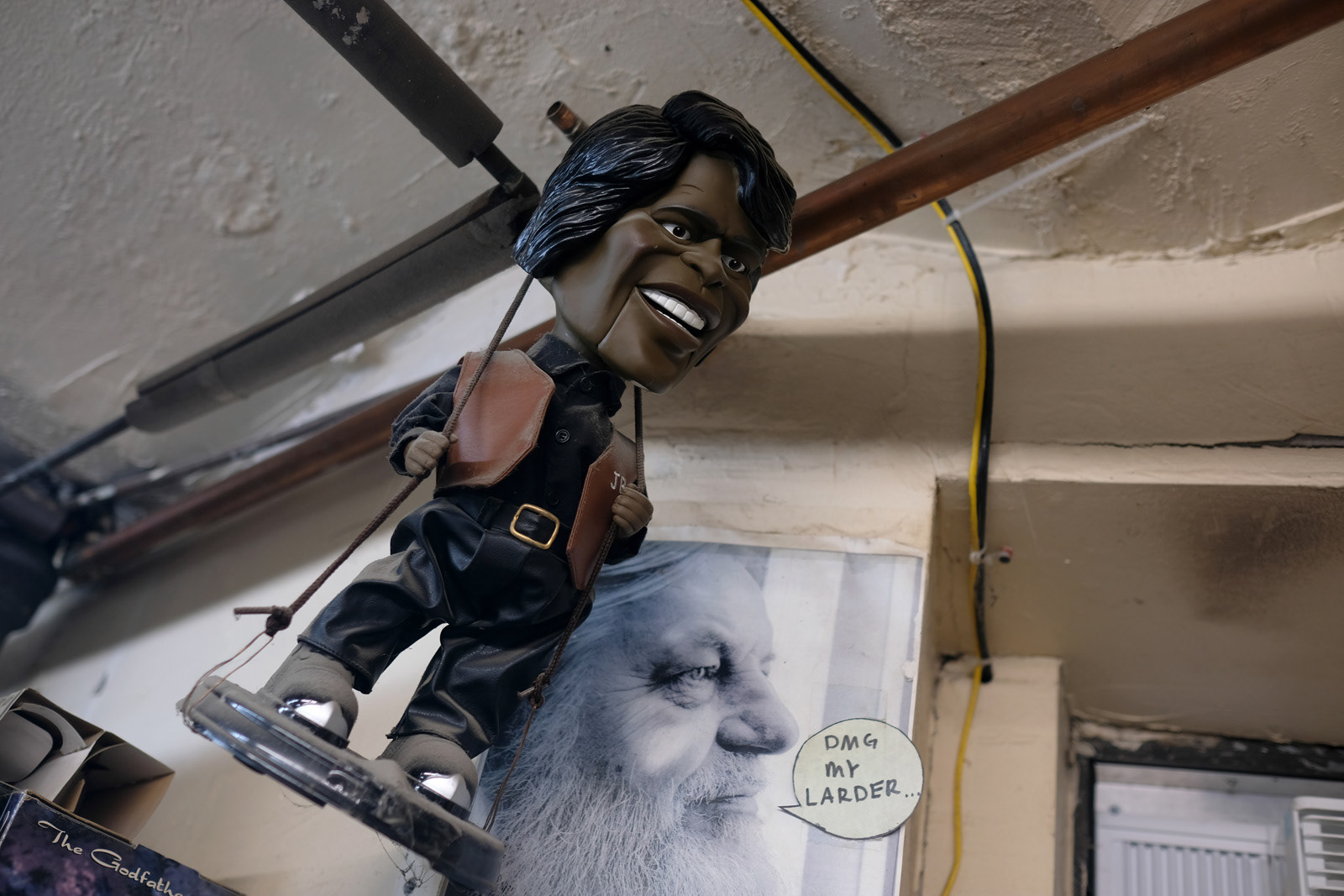

Bruce Lee Gallanter outside and inside the DMG. All photos: Hari Adivarekar

“It's an open-ended thing. Downtown music is people not worrying about a genre,” explained Gallanter. ”They're gonna try to do whatever they want to do.They're gonna borrow from different genres.This way people don't put expectations too much. When you play jazz, people expect you to play in a certain way.” The DMG provided a platform for artists playing genre bending free music that encompassed avant-garde jazz and contemporary composition, experimental, and improvisational music from around the world.

Mark Daterman (R) and Bob Nusso play a soulful set at the DMG on November 15, 2022

Gallanter always has a lot of time for his customers, often breaking into detailed musical conversations

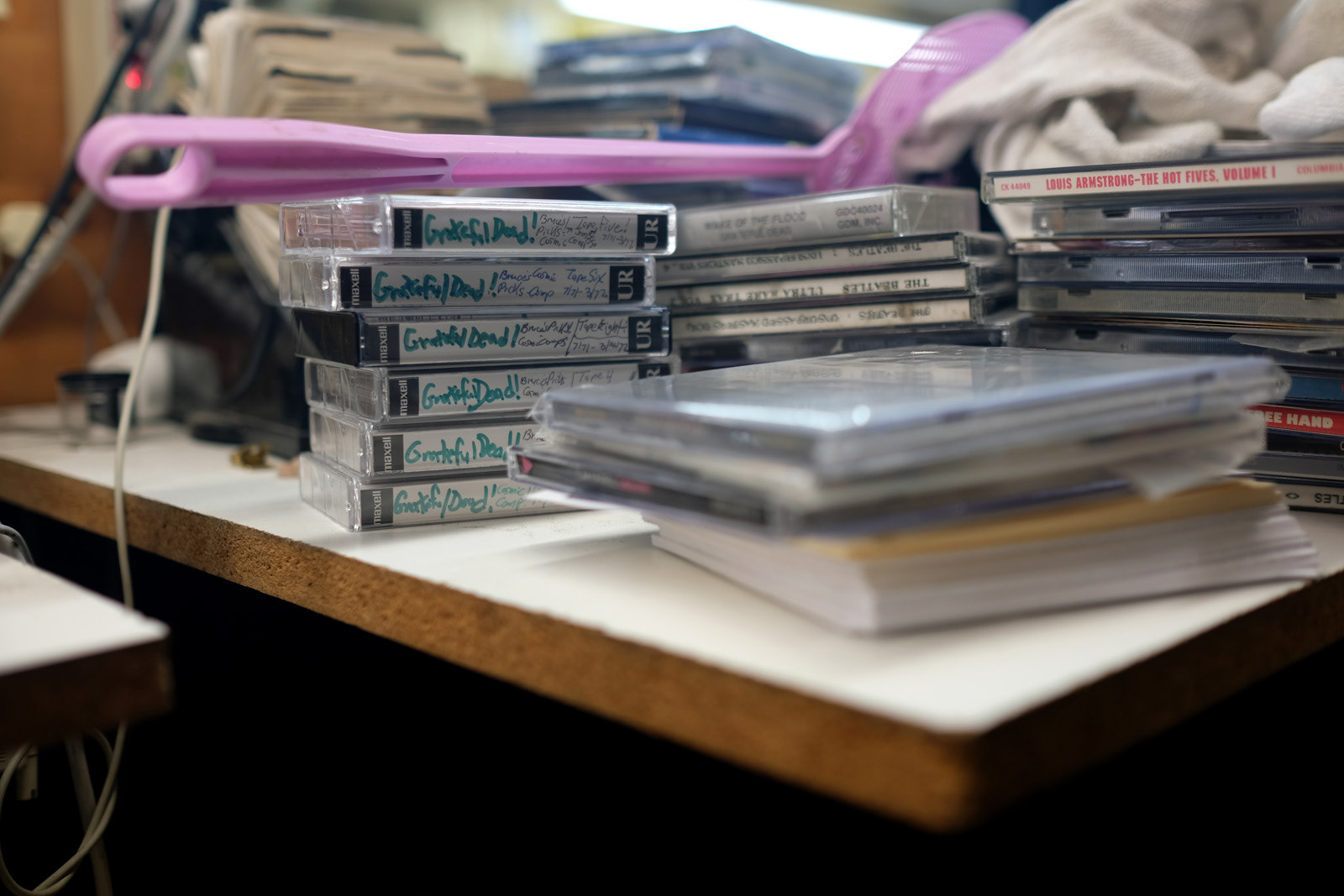

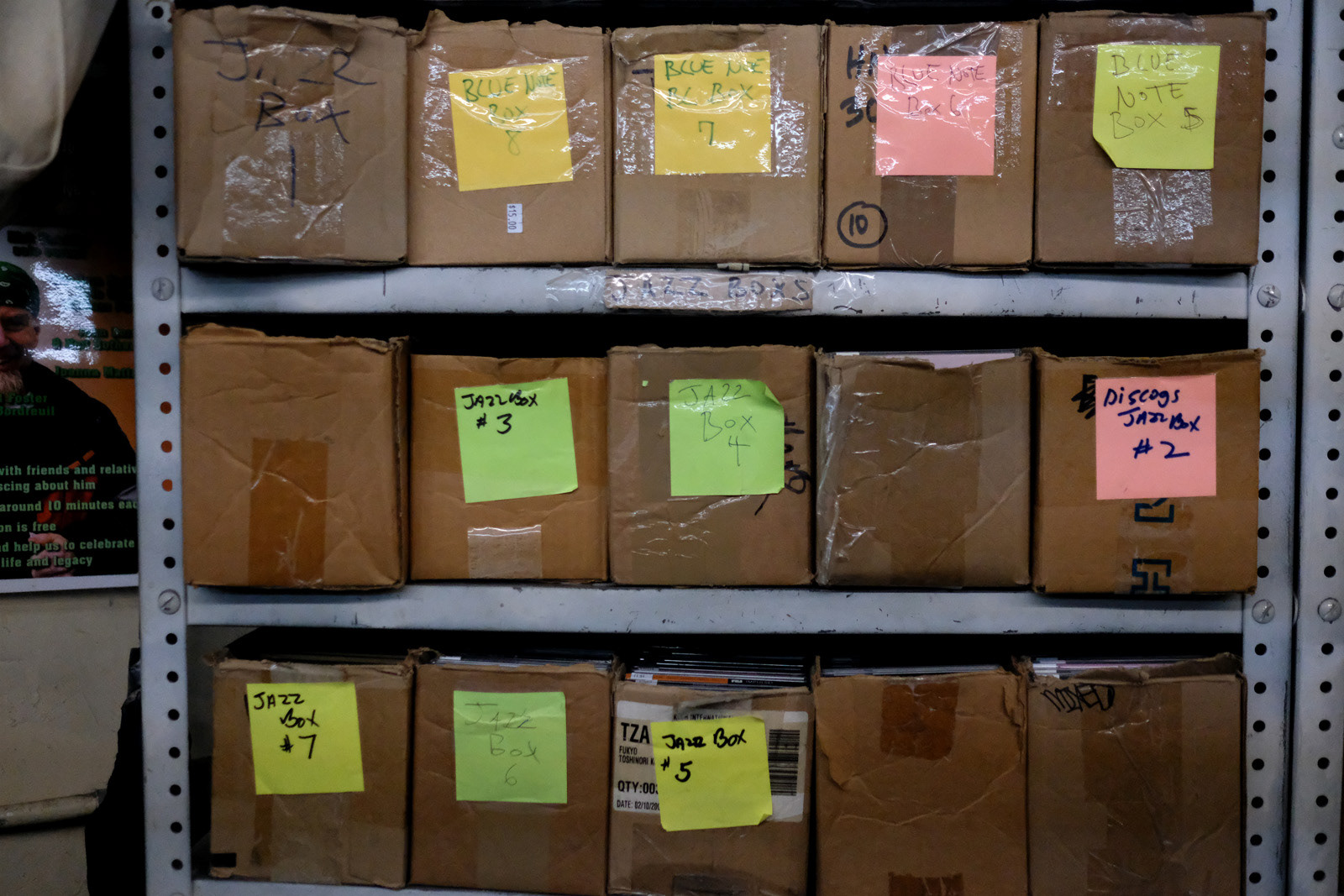

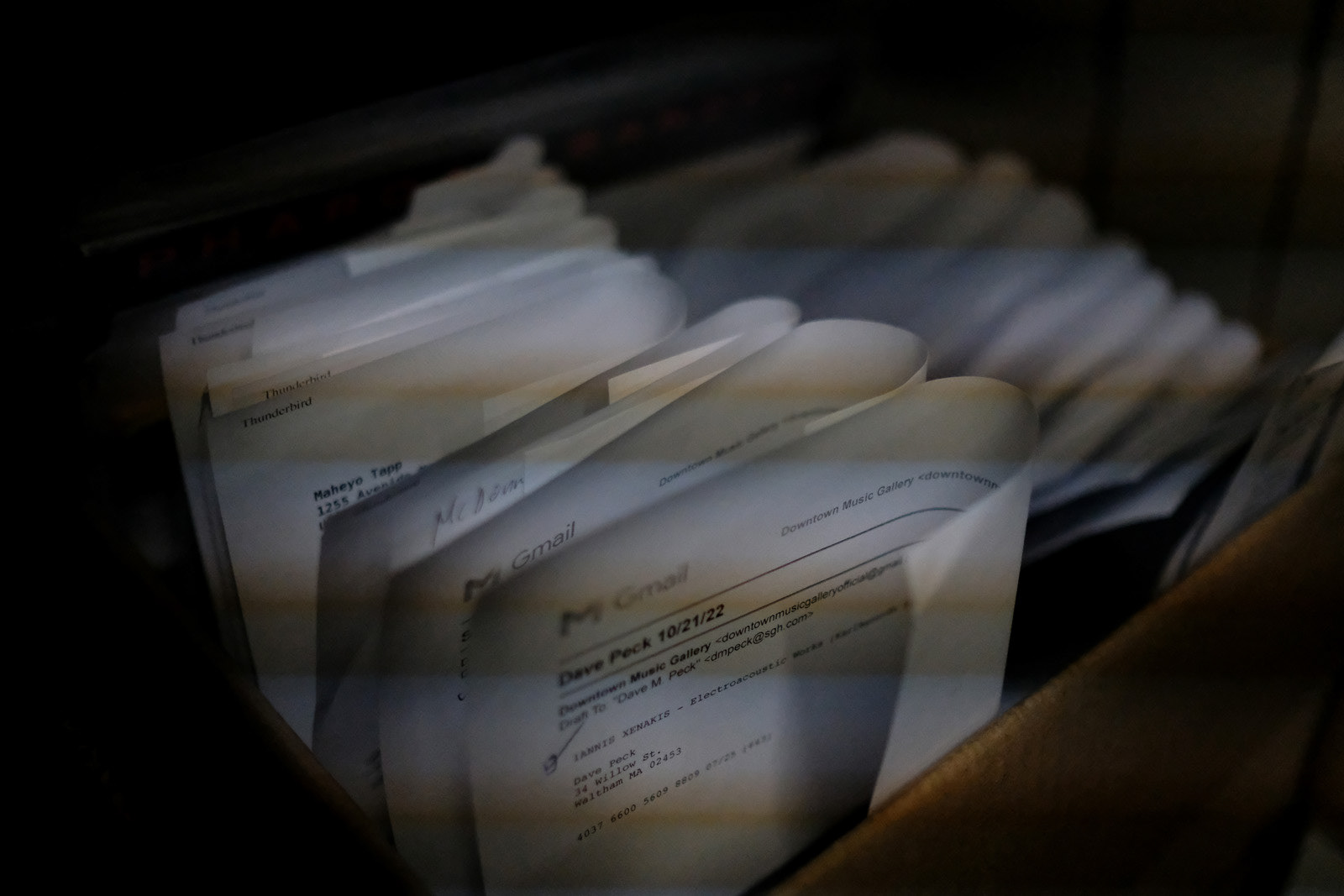

Every available space in Gallanter's modest apartment in Rahway, NJ, was stocked with his personal music collection.

Gallanter introduces guitarist Max Kutner. He shares an affectionate relationship with all the musicians who perform at the DMG.

Gallanter spells out his immediate challenges and how you can help him and the DMG