Prahlad Tipanya performs for a crowd of over 20,000 people assembled for an all night mehfil, in a field near the village of Rupakhedi

Moora Lala Marwada from Kutch, breaks into song en route in our pink bus while Tim, who was in the midst of a spiritual awakening, was never shy to break into dance

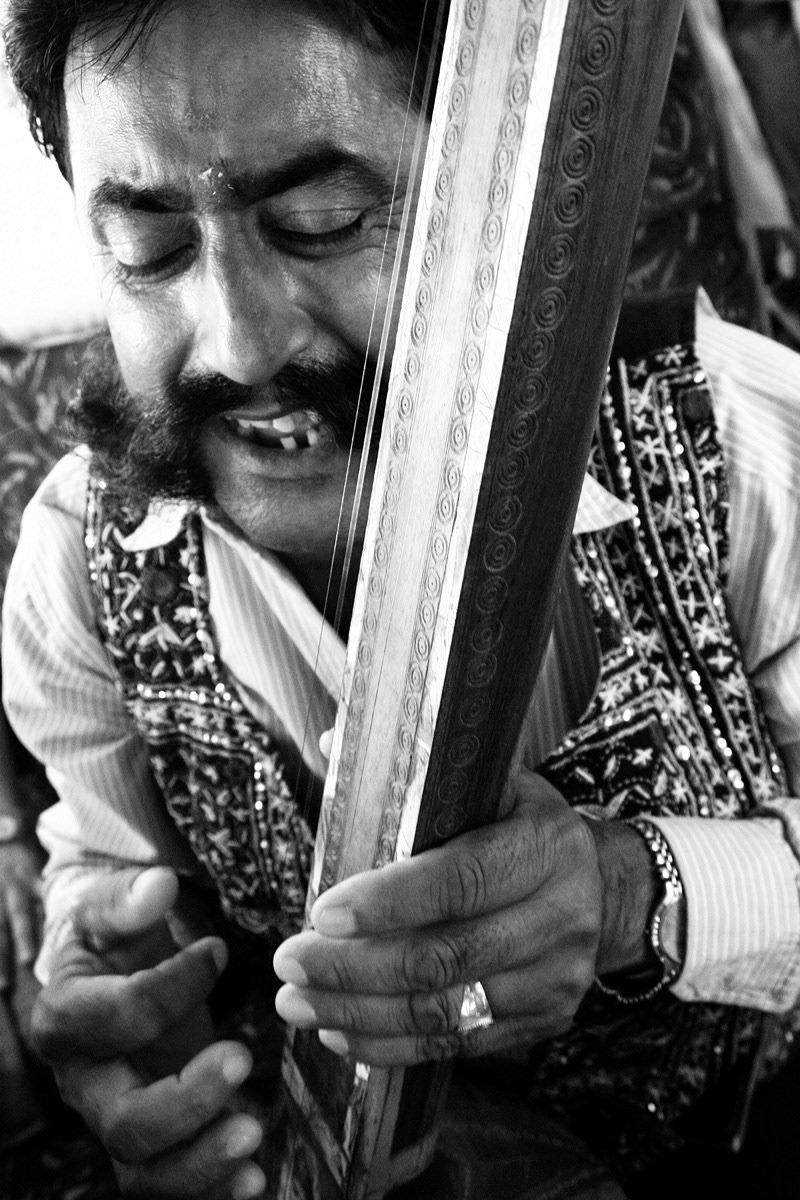

Mir Mukhtiyar Ali croons a sufi ballad to his wife over the phone, while on the road for the Kabir Malwa Yatra

Gopalji, a local teacher, folk musician and all round loving person, can’t contain his joy as he releases himself to whirls and grins as Shabnam Virmani performs

Mooralala Marwada and Prahlad Tipanya perform at Indore's Devi Ahilya University Auditorium

A kabir sant dances during the Luniyakhedi Shubh Yatra

Two young girls run through a field adjoining the stage area for the Luniyakhedi round of the Malwa Yatra.

Impromptu and larger scale performances were the norm at Prahlad Tipanya’s Kabir Smarak Seva Shodh Sansthan, an ashram in Luniyakhedi, a tiny village in the Malwa region of interior Madhya Pradhesh. An audience of a thousand had gathered for the all night performance.

I was neck deep in my last hours at the first ever Malwa Kabir Yatra in March 2010. I sat in a large room in Prahlad Tipanya’s Kabir Smarak Seva Shodh Sansthan, an ashram in Luniyakhedi, a tiny village in the Malwa region of interior Madhya Pradhesh. His wife Shanti Devi, a deep and practical thinker, served me hot parathas and dal baati as Prahladji watched me like a doting uncle, his ubiquitous half-smile shining through a meticulously trimmed white moustache.

Over the last week it seemed like he was everywhere at once. As a gracious host, a powerful performer, a philosopher and demi-saint spreading the practical teachings of Kabir. As a master of ceremonies having Indore’s few hundred or Rupakhedi’s 20,000 listeners camped for the night in the middle of nowhere, enraptured by his every word. In Luniyakhedi, his home, he is so much more. “The Luniyakhedi satsang organised by Prahladji has been on a large scale for 18 years. The idea was to take the philosophy of Kabir to the people in a larger scale,” says his son and percussionist Ajay Tipanya. For 18 years, he has thrown open the gates of his ashram to thousands of people, giving them blankets and mattresses with a giant shamiyana for shelter and food thrice a day for two days. All absolutely free. I was part of the first group of outsiders on the yatra. Two weeks ago when the fifth Malwa yatra finished, I had the opportunity to reconnect with Shabnam Virmani and Ajay Tipanya over the phone.

The idea of having a yatra was first hatched on an Amtrak train screaming through the wilds of Canada in 2009. “The yatra first took shape with the impulse to share the films of the Kabir Project with village audiences. Then cities, the US and Canada as well. Ajay and I were talking about how we could take these films back to the villages and people of Malwa, where they were shot,” says documentary filmmaker Shabnam Virmani, founder and director of the Kabir Project, speaking from her edit room, where she’s currently cutting her latest documentary. Over the last decade she and and the project have travelled across India and to parts of Pakistan with the sole objective of capturing the different manifestations of Kabir’s poetry in this vastly varied regions and cultures. Award winning films have resulted along with a growing community of Kabirophiles and Shabnam’s own immersion as a Kabir performer.

She says, “We then added the idea of it going from one village to another. The second addition was inviting artists from other places and states. We wanted to show the diversity of Kabir, by including musicians who sang in different languages and who were from different religions. It was also about having connections between rural areas of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat and other rural areas rather than make rural films only for urban audiences. I wanted to let the Kabir in Gujarat speak to the Kabir in Rajasthan and so on.”

During that first yatra that I attended, there were teething problems, some of which endure. But Shabnam says without guile, “There is roughing out and we never promise any comforts but there’s a lot of soul and heart. Some things work and some things don’t but that’s the charm. After all, yatra comes from the root word yatna which means suffering and there’s something to be learned from that.” As Prahlad Tipanya always reiterates, “What is the point of this outer yatra if it doesn’t trigger an inner journey?”

The yatra has also grown exponentially over the last five years. And with more urban people learning about the yatra, the number of buses on the tour has gone from one to two to three.

“There are many new performers coming in, many new yatris as well. There has also been a greater impact of the Malwa Kabir Yatra all over India. This year we had a group from America who came all the way just for the yatra and spent five days with us. We had people flying in from Kolkata and Hyderabad just to attend one day of the yatra in Bhopal and Indore. So we have this situation where people come from so far away, spending so much money just to hear the music and words of the performers. This year, it went off really well because we had help from the Madhya Pradesh government and the police,” says an excited Ajay on the phone from his home Luniyakhedi, deep in the heart of Madhya Pradesh just days after the 2014 yatra.

This isn’t just a journey for the attendees. Every year, the Malwa Kabir Yatra enables musicians, urban and rural, masters and neophytes to come together with a greater purpose than just holding concerts. “The performers don’t just come to perform, they come here to grow. These musicians really listen to each other and travel with each other on the bus and sing and learn from each other during the journey,” offers Ajay, who has been intimately involved in every single yatra in the dual role of organiser and musician. I can attest to the uniqueness of the bus journeys that obliterated all darkness and discomfort in the healing light of Kabir’s words set to joyous music.

This isn’t just a journey for the attendees. Every year, the Malwa Kabir Yatra enables musicians, urban and rural, masters and neophytes to come together with a greater purpose than just holding concerts. “The performers don’t just come to perform, they come here to grow. These musicians really listen to each other and travel with each other on the bus and sing and learn from each other during the journey,” offers Ajay, who has been intimately involved in every single yatra in the dual role of organiser and musician. I can attest to the uniqueness of the bus journeys that obliterated all darkness and discomfort in the healing light of Kabir’s words set to joyous music.

This happy inertia of motion spilled over into each venue at which our 2010 yatra halted. On stage is where the yatra is at its shimmering best. Even years later, the tunes and voices ring deep within the psyche. Moora Lala Marwada’s voice of the vast Kutch horizon felt like it came from deep within the earth to project outwards and pierce that endless nothingness. On his right, the formidable Parbat Jogi on the dholak, his calloused fingers coaxing cracking whips, gunshots and gentle trotting rhythms with equal ease. A couple of star-struck yatris requested a taal crash course to which he threw his head back and laughed, “If you can keep taal with a complete three hour concert from beginning to end without losing a beat, then come and ask me again. Taal takes discipline, it cannot come overnight.”

Shabnam Virmani bewitched the urban folk in Indore, her soaring voice and rapidly evolving musical skills amazing locals and yatris alike, all done while ensuring the tour motored on with few hitches. Mir Mukhtiyar Ali used humor and song to defuse a volatile situation in Bagli Chowk, where a bunch of drunk political ‘dignitaries’ were in danger of marring a yatra of peace and compassion. He and Moora Lala were the resident rock stars of the tour, whipping audiences up into a frenzy. Mukhtiyar has a way of marrying deep-rooted folk melodies and progressions with more formal classical phrasing or modalities. This makes for exhilarating performances in which you’re never quite sure where this mercurial and gifted vocalist will take you. He gleefully dances in the middle ground between the self-consciousness of the classical musician and the unabashed rawness of the folk artist, often breaking new ground in the process.

And finally there was Prahlad Tipanya, his voice sonorous and controlled, his mind razor-sharp to the possibilities of a quick discourse. He can sing the melodic pants off songs and dive into impromptu explorations of the lyrics, their true meanings and true worth to the audiences that throng his concerts. At Rupakhedi, dozens of people had the same answer when asked what made them leave their homes, cram into Tata Sumos and spend a night in the cold, huddled around fires. “Hum Prahladji ke liye aaye hain (we are here for Prahladji),” is the only reply, accompanied by a childlike grin, every single time.

Both Shabnam and Ajay are quick to point out that Prahladji’s engagement and study of Kabir goes way beyond the caste system, even though he is a Dalit himself. “The scheduled castes have carried the voices of Kabir for 600 years so it isn’t surprising that he is still associated with them. But Prahladji resists from filtering Kabir only through the Dalit voice. He speaks about all kinds of divides, not just that between upper caste or lower caste. There is no separateness for him. That’s a truly Kabiran property. Yet, what he does is political and when he is speaking on caste he isn’t soft-peddling either. It’s a subtle thing, it’s a larger human quest,” explains Shabnam, who has trained as his disciple for years.

So it isn’t surprising that Shabnam Virmani, Ajay Tipanya and all those involved in the Malwa Kabir Yatra or the Kabir Project exhibit a mindfulness that keeps them questioning their own motives. “When one starts something like this, there is a freshness,” says Shabnam. “Then, there’s always a danger of it becoming an institution and then the danger of innocence getting lost once it becomes routine. At the moment we all at the Kabir project community have to ask ourselves what is the meaning of these yatras? Why are we making it larger and larger? Are we losing something? Is it becoming a fad? How much is our yatra facilitating deeper engagements?”

As long as these questions are always on their minds, with the songs and words of Kabir on their lips, there is a guarantee of innocence and unbridled joy, of journeys external and within, of communions between people from different universes, of a humility that comes with a yatra that embraces all with no judgement.

Once I finished my food, Prahladji himself drove me to the train station. A tiny gesture made by a very big heart. He might have been exhausted after the gruelling yatra where he played so many roles. He might have been focused on his upcoming classes. But at that moment he was making sure that yet another yatri was sent safely on their way, to begin their internal journey, now that the external one was done.