One person by his bedside that day was not a family member. Somashekara Chari encouraged the family to take Kumar to Karunashraya, the pioneer Bangalore hospice that offers free palliative care for advanced-stage cancer patients who are beyond medical cure. Somasekhara might notionally be just the designated auto driver for Karunashraya, but he has been visiting the dying for almost two decades as an emissary from the hospice. He has also become an unofficial Karunashraya homecare manager in the last few years. That day, Somashekara cajoled Kumar into drinking a few sips of coconut water while cradling his head.

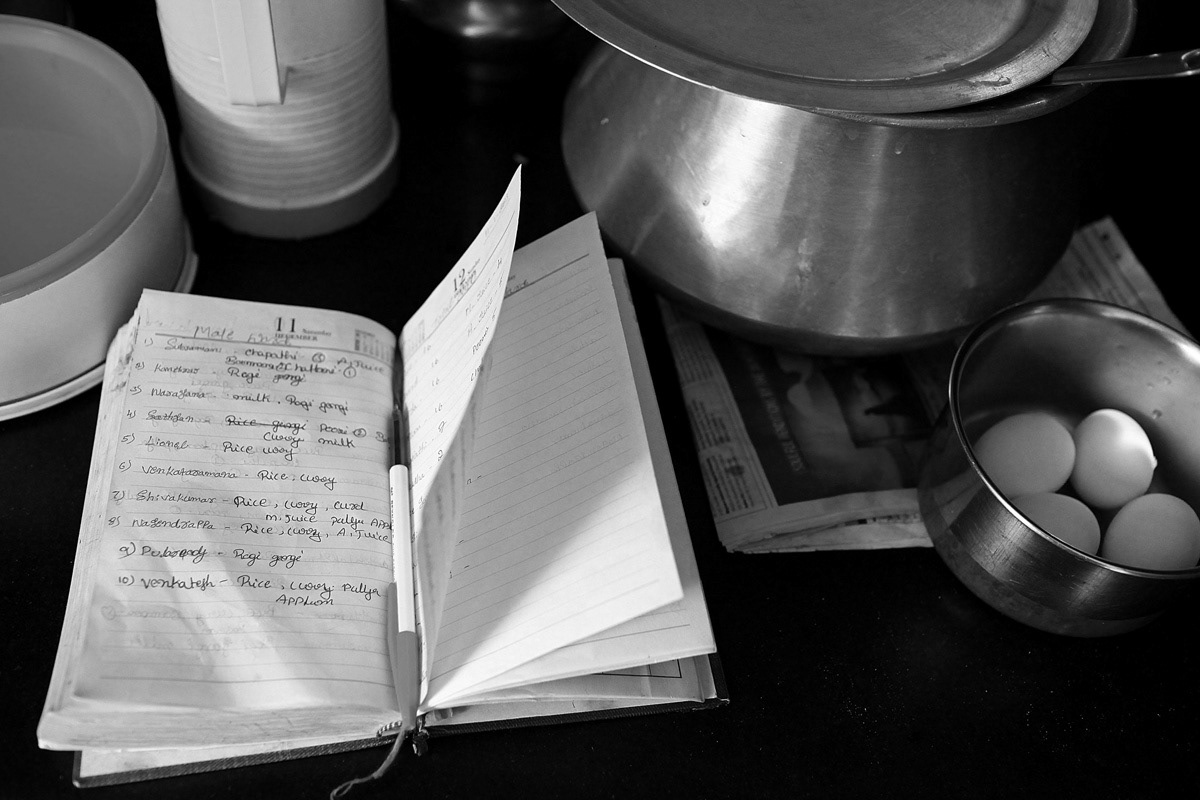

The Karunashraya homecare team visits 50 patients per week. Somashekara drives nurses in one of the two distinctive blue auto rickshaws.

The team drives to all corners of the city, no matter how remote or inaccessible, helping the poorest of the poor find peace and dignity before a painful death.

Karunashraya has offered free home care services for terminal cancer patients since 1995. It established an in-patient service in 1999 at its 50-bed hospice in Marathahalli, Bangalore. The hospice operates solely on cash and in-kind donations, which sometimes attracts strange items. Donors range from companies like the Tata Group and GlaxoSmithKline to concerned individuals.

Karunashraya also provides patients with images of Gods of all religions (but only if they ask for them). The emphasis here is on providing palliative care, which is a holistic approach that involves medical, psychological and even spiritual support to ensure a peaceful and dignified death for patients.

Home care nurse Pushpalatha treats a 27-year-old who was in the last stages of mouth cancer caused by chewing gutka. The nurses check vitals, change dressings and ensure correct medication is provided between visits.